Art as a part of life: An interview with Péter Küllői

A staunch supporter of Central European arts, a member of Tate’s Russia and Eastern Europe Acquisitions Committee, and the international board of advisors Kunsthalle Praha – philanthropist Péter Küllői hopes that the Czech capital could become an art hub for Central and Eastern Europe. In an interview with the founders of the new institution, Pavlína and Petr Pudil, he talked about his love of 1960s art and about why he wouldn't consider himself a collector.

Previously you were a very successful investment banker. Was it difficult to step out of the industry?

It wasn’t. When I was thirty-one, I decided that I would retire once I turn forty, without knowing how much money or what kind of success I was going to have. When we moved to London I told my children and my wife that I will stop when I turn forty, but it definitely wasn’t easy because of the ego element and the feeling of importance. So I accepted an advisory position in one of the biggest investment banks for another year, and I travelled to London every first Monday of the month.

After a while I realised that there was no challenge in it anymore, and I wasn’t even enjoying it anymore. So actually, it was a cleansing process. But it was the ego and letting this feeling of importance go that took a year – that was the toughest part.

Let’s move to the art field. How long have you been involved in art? And is your interest in art influenced by your parents and family?

I was brought up surrounded by art. My father was a surgeon and once performed surgery on an art dealer. He recommended the young surgeon to buy this and that. Some of them turned out to be very famous paintings, some of them turned out to be fakes. I even have a fake one on my wall because I just love it and it’s a part of my childhood.

For me, art was never an investment but a part of life. Then it became a journey – and it has been quite a journey. First I admired figurative painters, mainly from Hungary, then I became more and more interested in conceptual art – but it’s still a long ongoing journey. I have always loved art and considered it to be a part of life.

So do you consider yourself a collector?

I would not consider myself a collector. We have fantastic works in our halls and we have always lived with art. But I don’t collect because of the collection, I collect because I want to live with beautiful art, that’s my approach.

What has been your favourite artist or area of art that you have been able to purchase?

I am a big fan, and it’s no surprise, of the sixties. Not because I was born in 1960, okay, just as well, but also because of this whole change that has happened, when art had nothing to do with business. It was just pure joy. I am also a big fan of the Central European region in general. At the time the region was not very well-known, so I am really enjoying this kind of rediscovery that is happening these days. Some of these artists from the sixties are my favourites. You will not be surprised that Dóra Maurer is very close to my heart.

We live in a globalised world. Do you think we can still talk about national art in the current climate?

I don’t think we can. If you look at the ‘60s or after the Second World War, we can talk about regional art. I will never forget when we had the Bator Tabor auction in Bratislava and Mr. Sýkora brought a piece of his work. He saw Imre Bak’s work and he started to cry – he and Imre had visited many places together when they were young. So, it’s a good example that it has always been regional, we just looked at it with a local mindset.

Today, for the younger generation I think it’s global. I don’t see it too much as an art of a country. But the region is very important. I think that if the approach is regional, it has a greater chance of succeeding internationally. What I learned from my involvement with Tate, the Met and others, is that they look at us as a region, not as a country. One of the reasons I am so honoured to join the advisory board of Kunsthalle Praha is because it has the right approach in this respect.

There is a rumour that Henry Kissinger once said: ‘Who do I call if I want to speak to Europe?’ The same applies if a museum in the United States wanted to talk about Central Europe – who should they talk to? Where should they go? Kunsthalle Praha could very well be the place they would come to. I don’t see any other approach as professional and international.

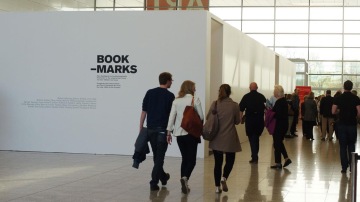

In 2018, there was a fantastic show called Bookmarks in London, which was led by you and it was about Hungarian art from the 20th century. Can you tell us more about it?

The idea for the Bookmarks show came from a Tate visit eight years ago. The first stage of the trip took place in Budapest and the question was what to show them. Hungarian institutions were convinced that what they believe is a good quality of art should be agreed with by the world as well. Tate said in advance that they were interested in conceptual art of the ‘60s and ‘70s, but there was no place to see works from that period because the National Gallery was hardly showing any, and the Ludwig Museum was also showing mostly Western art and very limited regional art.

I met the three gallery owners in Hungary who were representing most of the Hungarian neo avant-garde artists and explained to them that they shouldn’t fight each other but that only working together can make a difference. “Let’s do an exhibition of the neo-avant-garde. I bring the sponsors; you do the exhibition.” After that, the Tate group came including Frances Morris and they loved what they saw. I also got the confirmation that this is something special from Tate and Frances Morris and this was a very strong reassurance that gave us the confidence to move forward.

I then approached Daniel Hug, who is a good friend of mine and a director at Art Cologne, and he said we should show it there. The following year it opened at Art Cologne with 75,000 visitors. It was a big success. With the help of András Szantó, the galleries did an exhibition show in New York, which also played an important role in getting Hungarian artwork to the Met.

The next step was London. I think it is important to appreciate the level of cooperation of the three galleries involved. Two of them had bought many key pieces early enough on the secondary market, so they had a wonderful collection. Also, immensely important was the encouragement from Frances Morris and the Tate team, and the connections with Daniel and András.

And why do you think there aren’t many similar shows focusing on Central European art in Western Europe yet?

Art from the region is being discovered more frequently, but the exhibitions are fragmented and also not regional. For example, Tate said a couple of years ago that they were only doing solo shows or global exhibitions. Central European works became a part of international exhibitions and there are more and more solo shows like Dora Maurer at Tate. Tate will also have solo shows for Abakanowicz and Bartuszová.

So, it is coming along but slowly. I really believe that it can be speeded up by having a regional version of Bookmarks, showing the best Czech, Slovak, Hungarian and Polish artists together. Most of the US institutions, with the exception of MoMa and the Art Institute of Chicago, don’t have anybody who is focusing on Central Eastern European art. A fantastic regional show like that would help a lot.

For quite some time you have been a friend to the Tate, and have worked with a number of other institutions. What do you think is the biggest challenge for institutions in the near future?

An interesting question. A couple of things. First of all, funding, at a time when the state is withdrawing and the private is stepping in. Certain questions arise; Is it okay if those contributors don’t want their name exposed? Is it okay if an individual or corporate is giving money yet potentially harming the reputation of the institution? That’s also an issue in London. Because many people from all over the world move to London and the sources of the money are sometimes questionable.

The second thing that is a challenge is digitalisation. How to appear cool for the next generation? How to bring those people into the institution? Whether to reach the people directly using virtual reality or augmented reality? I think AI will happen very soon for the art world, and it will be a challenge for these institutions. I believe that Tate is one of the leaders and that’s one of the reasons why I love them. They are approaching everything in an open-minded international way.

MoMa has also changed how they exhibit their works and are working in a similar way. That’s not the case for most museums. It’s a very slow process. If you look at MoMa, in my view they are partly a real estate company, and they get a lot of funding this way. So, they have the flow of money. Some other major institutions have built a successful and diversified funding strategy. For some bigger and many smaller institutions, it’s very difficult to ignore the pressure that comes with dependence on the support of board members and some key supporters, in terms of what they like and what they donate. It’s not easy to manage this kind of funding and these kinds of various interests and influences. MoMa has the freedom and Tate has also built up a strategy that allows freedom. But there are not many who can do that.

So, you were born in Hungary, which means in the same region as the Czech Republic with its capital Prague. What’s your history with Prague?

I was born in 1960. When I was eight my parents took me and my twenty-one-year old brother for a vacation to the Tatra Mountains. And that’s when the Russian forces together with the Hungarian forces occupied Czechoslovakia. As I was a child and my parents were protecting me, I wasn’t very worried. But then, I learned that the strong feelings against the Hungarians were justified to a certain extent. How to get back to Hungary? We had a Czechoslovakian car in front of us and a Czechoslovakian car behind us. And that is how we moved back to Hungary. I still have vivid memories of going along by the tanks and all of that. It is a very strong memory for me of 1968 and I have a strong feeling of sympathy for this country, which at that time was one country and now is two countries.

I felt at home and I still feel at home here. Even for Bator Tabor the plan is that the Czech Republic and Slovakia should be part of our home. For many reasons I believe that a region needs a hub. Prague in my view could become the art hub for Central and Eastern Europe.

For me borders don’t exist. You know there is research that examines how under-twenty five-year-olds identify themselves. It was done in Germany – their first answer was that “I am a planetarian”, number two that “I am a Berliner” or whatever city they were from, number three was that “I am a European” and number four was that “I am German”. So, when I am asked, even though I’m not under twenty-five…

You’re twenty-five in your mind.

... That I am. But I wouldn’t say Hungarian first. I am not saying planetarian either, but I would say a European, a Central European, from Budapest… maybe Budapest and Hungary together.

The interview was led by Pavlína and Petr Pudil, the founders of The Pudil Family Foundation

The full interview is a part of Kunsthalle Conversations, a book we will release in 2021. The publication consists of interviews with ten inspiring personalities who significantly contributed to the development of the vision of Kunsthalle Praha and to our programme.

PÉTER KÜLLÖI (HU)

An entrepreneur, philanthropist, and art collector. As an active supporter of the Hungarian and Central European arts he has promoted the global recognition of the region with a number of international institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tate Modern and more. For the past seven years he has been a member of Tate’s Russia and Eastern Europe Acquisitions Committee, and in 2018 became co-chair. He is currently a member of Kunsthalle Praha’s advisory board, where he offers insights regarding strategy and dramaturgy. As a philanthropist he is a board member of the Common Purpose Charitable Trust and SeriousFun Children’s Network.