An inconspicuous palace of electricity – The history of the Zenger substation

The inconspicuous palace in Klárov, built at the foot of the Letná geological formation, where Chotkova Street opens up, was never really a palace. If this were a building of a residential and representative character, it would be obvious to everyone at first glance that it lacked a suitably conceived main entrance. But there was no need for any kind of grand, ceremonial presence at all, because this was not the residence of any noble family, nor had it been used by any respected institution. It was a palace where electricity hummed in the past. And electricity does not enter through a door, but through cables.

Zenger's Transforming and Rectifying Station at Klárov, as the building's exact name is, belongs to a large set of buildings whose construction was initiated and financed in the interwar period by the Electric Company of the City of Prague. This leading city enterprise, headed by the far-sighted chairman of the board of directors Eustach Mölzer, played a key role in the modernization of the Czechoslovak capital.

The efforts of the Electric Company’s management mainly focused on the upcoming Sokol meeting, which was to take place at the beginning of July 1932 in Prague at Strahov Stadium. Tens of thousands of visitors were expected to attend the event, and were mainly to be transported by trams up the long hill. To ensure this service, it was necessary to have reliable power distribution and the key node in the Prague network was the Zenger Substation in Klárov. During the 1920s, preparations for its construction were at their peak.

-

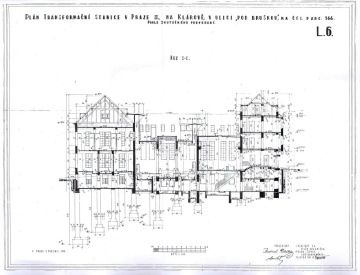

Archive plan of Zenger's Transforming and Rectifying Station

-

Zdeněk Pešánek

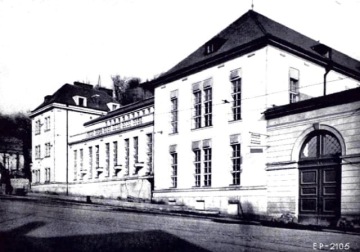

Between 1929-1932/1934, architect Vilém Kvasnička cloaked an industrial building at Klárov in a Classical morphology, thus sophisticatedly solving the difficult task of how to conceive such a building in the historical environment of the Lesser Town. This approach was not at all a given, however. Looking at other buildings instigated by the Electric Company, it becomes clear that this progressive company preferred modern morphology for its buildings. This is particularly evident at the corporate headquarters in Prague Bubny, which was designed by Adolf Benš and Josef Kříž and is hailed as one of the peak expressions of functionalism.

Using Classicizing forms for the exterior of the Zenger Substation was a sensitive solution for the completion of the city block immediately neighboring the Empire style palace of the former Klárov Institute for the Blind. Vilém Kvasnička therefore, for the modern industrial building, drew on the same formal source as the designer of the neighboring building, without resorting to an old-fashioned, historicizing artistic expression. On the contrary, his architectural handwriting in no way denies the period of its construction at the turn of the 1920s – 1930s.

Yet Vilém Kvasnička did not hesitate to suppress some typical Neoclassical features for the sake of the result. For example, he did not use a symmetrical layout for the building, which would be markedly problematic on an almost triangular plot. Evidently this is why the architect artfully distributed the composition of the building to use as much as possible of the plot. As a result, the Zenger Substation building creates an imaginative array of materials divided according to their purpose, while respecting the natural relief and configuration of the local development. This makes Kvasnička’s approach unique—it honors functionalist principles that are unified in the overall expression of the building using Neo-classical morphology.

-

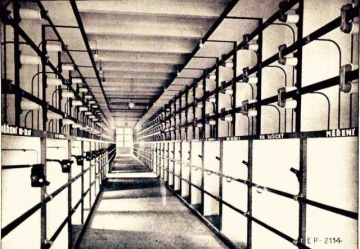

View of the transformer station interior

-

Construction of the cable channel

-

Zdeněk Pešánek, four light kinetic sculptures from the cycle One Hundred Years of Electricity, ©Monoskop.org

-

Zenger's Transforming and Rectifying Station

The main facade of the Zenger Substation was to be decorated with the extraordinarily inventive work of Zdeněk Pešánek, whose installation never took place. The original intention was long indicated by empty corbels, which were supposed to be fitted with four light kinetic sculptures inspired by one hundred years of the history of electricity. Pešánek wanted to achieve the visualization of electric energy with the help of neon tubes and five hundred colored light bulbs, which were also to be "the medium of their own melody of light". This melody was to play at regular intervals and last for over two minutes. In 1936, Národní listy informed its readers that Prague would receive "an original work in a completely new art form and technical field, a kind of which we have not yet found anywhere, even abroad."

Pešánek's innovative vision, however, never lit the facade of Zenger Substation. In autumn, the entire set of four kinetic sculptures was exhibited in Prague's Museum of Decorative Arts, and in 1937 Czechoslovakia also showed them off at the international exhibition in Paris. After the exhibition ended, however, the work did not make it back, unlike another of Pešánek's sculptures, which decorated Edison Transformer Substation. And so, the inconspicuous palace of electricity in Klárov never became the bearer of a very striking piece of Kinetic Art.

The historical photographs come from the publication of Zenger's Transformation and Rectifying Station published by Electric company of the City of Prague in 1932.

Vendula Hnídková, the authoress of the text is an historian of architecture.